Flint water causes citizens to become severely ill

Sincere Smith, 2, of Flint, Mich., is one of three children living with his single mom Ariana Hawk, 25. He is suffering from a severe skin rash that his mother believes is due to bathing in the contaminated Flint water. (Regina H. Boone/Detroit Free Press/TNS)

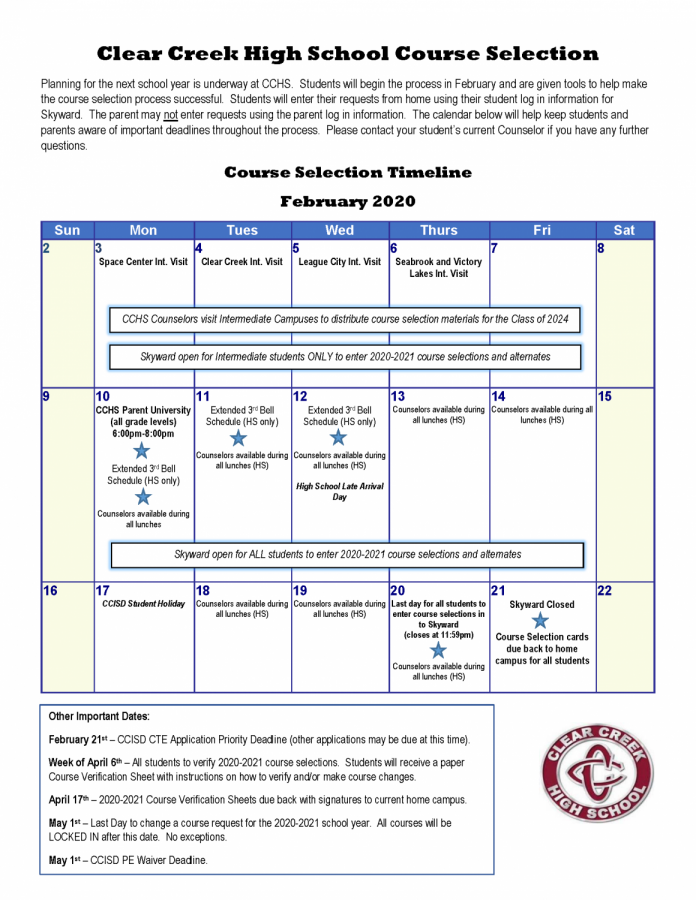

March 3, 2016

The city of Flint, Michigan has been pumping drinking water heavily contaminated with lead to its residents ever since an April 2014 switch from Lake Huron to the Flint River as the main water source in order to save money. The Flint River water proved to be highly corrosive, damaging outdated lead pipes and polluting the water with much more lead than is legally allowed or safe.

The situation came to national attention in early 2016 when a federal state of emergency was declared in Flint. Despite switching water sources back to Lake Huron in October 2015, lead levels are still too high in the tap water, rendering it undrinkable and unusable. Although the state and National Guard are now handing out filters and bottled water to residents, thousands of children have already been exposed to toxic levels of lead.

The EPA limit for lead in drinking water is 15 parts per billion. Water is considered toxic waste when lead levels exceed 5,000 ppb, however, some houses in Flint measured at a level of 13,200 ppb. Lead poisoning is known to impair cognitive function, shorten attention span, and spur antisocial behavior. Many kids in Flint are already considered “at risk” due to the extreme poverty of the city, and “neurological and behavioral effects of lead are believed to be irreversible”, according to the World Health Organization.

The switch to the Flint River was supposed to save the financially troubled city one million dollars a year. However, the river water was tainted by decades of far runoff, sewage, and industrial effluent. Locally, the river was known as “General Motors’ sewer” due to the automobile manufacturer’s extended use of and dumping in the river. The water proved to be difficult to sanitize due to its high levels of chloride, which is corrosive to iron. Corroding iron consumes chlorine, which is the main chemical used to make water drinkable. River water is also 12 times as corrosive as Lake Huron water, which led to the noxious element leaching into the water supply of residents’ homes. General Motors themselves switched to Lake Huron water in October 2014 because they were worried about the tap water corroding engine parts.

After the issue came to light, many concluded that the city had been neglected due to its population of mostly poor minorities. 57% of Flint’s population is African-American and 41% live under the poverty level, according to the U.S. Census.

“Would more have been done, and at a much faster pace, if nearly 40 percent of Flint residents were not living below the poverty line? The answer is unequivocally yes,” the NAACP said in a statement.

Some called the handling of the situation “environmental racism” because race and poverty factored into how Flint wasn’t adequately protected and how its water became contaminated.

“While it might not be intentional, there’s this implicit bias against older cities — particularly older cities with poverty (and) majority-minority communities,” said Democratic U.S. Rep. Dan Kildee, who represents the Flint area. “It’s hard for me to imagine the indifference that we’ve seen exhibited if this had happened in a much more affluent community.”

However, state officials, including Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, disagree. While he admitted there were “major failures” in the process, he blamed it on bureaucrats, specifically “a handful of quote-unquote experts that were career civil servant people that made terrible decisions.”

Attorney General Bill Schuette is currently investigating the situation, including a class-action lawsuit that alleges the state Department of Environmental Quality did not treat the water for corrosion in accordance to federal law.

He is also addressing the issue of residents continuing to be billed for their water use, despite the fact that it is toxic and unusable. He has said that his office has begun investigating steps to provide financial relief to the people of Flint.

“I would certainly not bathe a newborn child or a young infant in this bad water, and if you can’t drink the bad water, you shouldn’t pay for it,” Schuette said.